Last updated on September 4th, 2024 at 02:00 pm

Take Home Points

- Hypothermia is based on clinical symptoms + core temperature

- Most cases of hypothermia are resolved with external warming techniques

- In the sick hypothermia patient, be prepared for a LONG and modified resus

- In the sickest patients, ECMO is the end goal

As a kid from Phoenix, Arizona, treating hypothermia was never in the forefront of my mind growing up. However, moving to DC for Emergency Medicine residency brought it into the forefront. Whether it’s someone who spent too much time bobsledding in front of the Capital (a tradition protected by the official rules of the Capital grounds!) or an undomiciled individual with severe hypothermia due to a night spent outside, unprotected in the freezing weather, GW seems to experience the full range of presentations. In this post, we’ll break this down into each stage of hypothermia and their treatments, as well as some pearls for each presentation.

In a very generalized view, a patient is considered hypothermic if their trunk feels cold and/or core temp is measured to be <35°C/95°F. However, the severity of hypothermia is defined by the symptoms exhibited by the patient. Although we often talk about specific degree cutoffs, patients can have more severe presentations at higher temperatures. There has been debate about the best classification system, but we’ll use the one below.

You should also keep in mind the cause of hypothermia: primary or secondary. Primary hypothermia is a simple environmental exposure, when heat production in an otherwise healthy person is overcome by the stress of excessive cold. Secondary hypothermia, on the other hand, is due to impaired thermoregulation (ex. – sepsis, hypothyroidism, hypoglycemia, intoxication, etc). It’s key to gather history if able, including mechanism of injury, any substance misuse, the area patient was found/access to shelter. 1–4

Finally, the way you measure temperature matters. External thermometers are useless in hypothermia (ex. – oral, auricular, temporal). Rectal thermometers need to be placed and placed correctly (probes should be inserted to a depth of 15 cm). In patient who are intubated, consider esophageal probe lowered to lower third of the esophagus or bladder probe. There are some data showing that rectal and bladder probes lag behind on true core temperature reading, so ideally place an esophageal probe.

Mild Hypothermia (35-32°C)

Considered at a temperature between 35 to 32 degrees Celsius (95 to 89.6 °F). It’s almost uniformly resolved with:

- Environmental change (especially with taking cold/wet clothing off). A favorite at our shop is to place them in the trauma bay which is ungodly hot at baseline due to it being a trauma bay

- Blankets, heat packs/warmed water bottles wrapped up

- Consider the Norwegian “burrito wrap” [not a made up term!]: heat packs -> foil wrap over patient -> blankets over patient

- Warm sugar-containing drinks to encourage shivering

- Covering head (scalp loses a lot of heat)

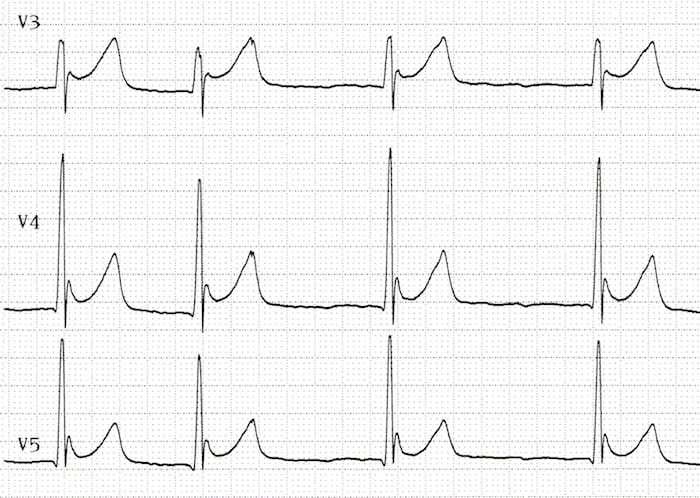

The core temp will tend to increase about 1°C/hr using these methods, therefore only requiring a few hours to achieve normothermia. During this time consider a workup to rule out secondary hypothermia, including a fingerstick, electrolyte studies, thyroid studies, and an EKG. Classically, the EKG will show a wide QRS, prolonged PR and QT intervals, and Osborn waves (J waves) aka the “hypothermic hump”.

Moderate Hypothermia (28-32°C)

Considered at a temperature between 28 and 32 degrees Celsius (82.4-89.6°F). Mostly treated with environmental change (clothes off, blankets, indoors) as well as a forced air re-warmer (Bair Hugger) or other commercial device to accelerate the rate of rewarming. Consider minimally invasive internal re-warming methods like O2 via high flow nasal cannula heated to 40-45 degrees Celsius and warmed fluids. Of note, warmed fluids maintain current temp however many hypothermic patients are also dehydrated due to a phenomenon called cold diuresis! Microwaving fluids is controversial, consider placing them in a Belmont device or your blanket warmer.

Severe Hypothermia (<28°C)

Here is the meat of the topic. I’ll break this into two stages: severe hypothermia with a pulse and severe hypothermia without a pulse.

Severe Hypothermia with a Pulse

The risk of death and disability is unfortunately very high once your core temperature reaches <28 degrees Celsius (<82.4 °F). These patients are often markedly obtunded and hemodynamically unstable. Complicating your normal resuscitative efforts are a mosaic of physiologic abnormalities. Obviously, start with the treatments highlighted for mild/moderate hypothermia first. Simultaneously, assess your ABCs. If intubation induction/paralytics are needed, consider a half-dose for patients with temperatures less than 30°C (85°F) because the duration of the agents will be prolonged. Avoid succinylcholine given a high potential for hypokalemia in profoundly hypothermic patients. Additionally, avoid cardioirriatant sedative agents like ketamine when other options are available. Finally, when doing any procedure, be mindful about moving patient aggressively (this could mean moving the patient to/from CT scan) or using devices that agitate the heart (e.g. CVC) as these can precipitate ventricular arrhythmia.

Once the ABCs are addressed, activate ECMO early. Per the chart below, this is the gold standard technique for aggressive warming.

Recommendations vary as to acceptable transfer time to ECMO centers, with most recommending transfer if a center is within 6 hours travel time. If ECMO is not available, consider alternative invasive warming techniques like continuous rental replacement therapy (CRRT), peritoneal or thoracic lavage, bladder lavage.

Severe Hypothermia without a Pulse

Generally seen in those with core temperature less than 24 Celsius. If you’re at this phase, ECMO canulation should be a top priority. The phrase “you’re not dead until you’re warm and dead” is true, as there have been some incredible saves seen in the literature in profound hypothermia with hours of down time. Normal ACLS is going to get a little strange, but with good reason: each degree of core temp drop corelates to 6% drop in cellular oxygen consumption. Therefore, at about 28 degrees Celsius, demand is dropped by 50%! At 18 degrees Celsius, the body can tolerate cardiac arrest for 10 times as long as one at 37 degrees!5–7

With that in mind, start your code by slowing down. Given the decreased demands on the body, look for pulses for 1 minute as the patient can be profoundly bradycardic. Additionally, early arterial line placement is recommended to have direct measurement of arterial flow. Corneal reflexes are expected to be fixed and dilated at temperatures below 29 Celsius. “Rigor mortis” may not be true rigor, given the temperature of the tissue.

If you’ve confirmed a pulseless, hypothermic patient, then be prepared for a LONG code. Mechanical CPR devices are almost a must.

There is controversy concerning shocks and code meds in hypothermia. The American Heart Association, the European Resuscitation Council, as well as Brown et al (considered the gold standard review article in hypothermia management) recommendations are summarized below:

- AHA: If VT/VF is present then defibrillate. If VT/VF persists past a single shock, then it is reasonable to continue shocks per BLS algorithm. It “may be reasonable to consider” ACLS medications such as epinephrine. There is no role for atropine or cardiac pacing.

- ERC: drugs and defibrillation should not be used until a body temperature equal to or more than 30°C has been achieved. If used, drugs should be given at double the normal interval (i.e. epi every 6 min) until normothermia is achieved

- Brown et al. splits the difference: “The temperature at which defibrillation should firstly be attempted, and how often it should be attempted in the severely hypothermic patient, has not been established. If VF is detected, defibrillate according to standard protocols. If VF persists after three shocks, delay further attempts until core temperature is ≥30°C”

Equally as important, consider those who would not benefit from aggressive resuscitation. Patients long deceased patient that happens to be cold, those with profound dependent lividity, those completely frozen solid with non-compressible chest, submersion hypothermia (e.g. drowning victims), and those that asystole persists once >30 degrees Celsius is achieved. Though not common in DC, avalanche burial ≥35 minutes in patient with a snow packed airway, they are dead likely due to asphyxia. A lab cut off of a potassium level >12 mmol/dL is commonly considered an indication to terminate resuscitative efforts.

This post was peer reviewed by Dr. David Yamane, Emergency Medicine and Critical Care physician and educator at GW

Cite this post: Michael West, DO, Arman Hussain, MD. “CHILL OUT, BRO!: ED Management of Hypothermia”. GW EM Blog. July 1, 2024. Available at: https://gwemblog.com/hypothermia/.

Related Posts:

rMETRIQ Score: Not yet rated/21

References

- 1.Paal P, Pasquier M, Darocha T, et al. Accidental Hypothermia: 2021 Update. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(1). doi:10.3390/ijerph19010501

- 2.Brown D, Brugger H, Boyd J, Paal P. Accidental hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(20):1930-1938. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1114208

- 3.Dow J, Giesbrecht G, Danzl D, et al. Wilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Out-of-Hospital Evaluation and Treatment of Accidental Hypothermia: 2019 Update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2019;30(4S):S47-S69. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2019.10.002

- 4.Waasdorp Jr C, Bernier C, Gardner J, Mattu A and Swadron S, ed A, Swadron S. Primary Hypothermia. CorePendium. Published February 14, 2023. Accessed April 17, 2023. https://www.emrap.org/corependium/chapter/recQmTAapS9S5vTCh/Hypothermia#h.40xwy6d1fajg

- 5.Truhlář A, Deakin C, Soar J, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: Section 4. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances. Resuscitation. 2015;95:148-201. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.017

- 6.Vanden H, Morrison L, Shuster M, et al. Part 12: cardiac arrest in special situations: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122(18 Suppl 3):S829-61. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971069

- 7.Röggla M, Frossard M, Wagner A, Holzer M, Bur A, Röggla G. Severe accidental hypothermia with or without hemodynamic instability: rewarming without the use of extracorporeal circulation. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2002;114(8-9):315-320. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12212366