Last updated on September 4th, 2024 at 02:01 pm

Take Home Points

- Consider this diagnosis in patients who don’t have clear gallstone or ETOH etiologies of pancreatitis

- Check serum triglycerides and VBG. Don’t get confused with DKA or another anion-gap metabolic acidosis

- IV Insulin in the mainstay of treatment

- While plasma exchange may reduce serum triglyceride levels quickly, it is rarely necessary, and few patients benefit from transfer to apheresis centers

Case

- Your next patient in the ED is a 34 yo F with history of type 2 diabetes who presents with two days of nausea, vomiting, and epigastric pain. Her vital signs are significant for: HR 120, BP 130/85, T 99.0F, RR 22. On exam, the patient appears uncomfortable, diaphoretic, and has moderate epigastric tenderness without distension or evidence of peritonitis.

- Your differential is broad at this point. Does the patient have DKA, Gastroparesis, Pancreatitis, Cholecystitis, SBO? Do they have an intrathoracic pathology – basilar pneumonia, esophageal perforation, ACS?

- Your bedside POC Glucose comes back at 450. Maybe this is DKA, you think.

- The rest of your labs are as below:

- BMP: Na 133, Cl 95, Cr 0.8, BUN 10, HCO3 12

- LFTs: wnl

- CBC: WBC 13,000, otherwise wnl

- Lipase: 2000

- VBG: pH 7.37, PCO2 40, HCO3 26

- You obtain a CT of this abdomen and pelvis which indicates an acute interstitial pancreatitis and a RUQ US with a normal gallbladder without stones. You question the patient who reports never drinking alcohol and not taking any medications associated with pancreatitis.

- Now before we simply give antiemetics, parenteral analgesia and IVF and admit the patient to the medicine floor, you have a few more questions to answer that actually may change treatment and disposition.

- What is the etiology of this patient’s pancreatitis?

- Why do they have such wildly different HCO3 values on their BMP vs their VBG? Do they actually have an anion gap metabolic acidosis?

- What else am I missing here and how do I treat this?

“Any recent scorpion encounters?”

What is the etiology of this patient’s pancreatitis?

We’ll start with question one above. There are many causes of acute pancreatitis, but by far the most common that you will see in the ED are gallstone and ETOH associated. However the other major causes include: post-procedural (commonly after ERCP), medication-associated, and hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis. In fact, hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis accounts for about 10% of all cases of acute pancreatitis, and is what is ailing the patient in this vignette.1

But how do we get to the correct diagnosis? There are a couple of clues that can lead us in that direction. First: the right patient population. These patients commonly, but not always, have type 2 diabetes, are obese, and do not have the same risk factors of ETOH use or history of gallstones. Although, it is possible for someone to have an alcohol use disorder and still end up getting a hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis, so don’t completely rule it out. But if other etiologies of pancreatitis aren’t present on history, exam, and imaging, keep this diagnosis in the back of your head.

What is going on with those lab abnormalities?

Second, there are a couple peculiar laboratory anomalies that are caused by hypertriglyceridemia. Due to measurement errors for laboratory equipment used to run metabolic panels, a triglyceride level in the thousands can cause an erroneously decreased HCO3 level. The best way to tease this out is to obtain a blood gas sample because blood gas analyzers do not directly measure bicarb but rather calculate it using other measured substrates and the Henderson-Hasselbach equation. What this means is that blood gas HCO3 is not falsely skewed by the laboratory measurement errors. You can see this phenomenon in the labs above where the BMP has an HCO3 of 12, but it shows up at 26 on the VBG (which also returns a normal pH and CO2, indicating that you do not truly have the metabolic acidosis you first thought)

Profound hypertriglyceridemia may also return a pseudohyponatremia for similar reasons. This one is harder to tease out due to no other available assays to compare your sodium value to.

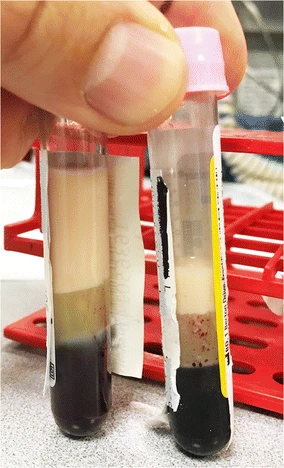

Once your suspicion for hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis is high, there are two ways to confirm your suspicion. First you can get a triglyceride level (which you’ll need anyways to evaluate for treatment response), but that can take several hours to result. Even quicker, you can call your hospital lab. Have them visually look at the sample to see if it is “lipemic” – this means that there is milky-appearing lipid within the serum.

Now that you’ve diagnosed hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis, how do you treat the patient and where do they get admitted?

How do I treat this patient?

The mainstay of treatment is lipid lowering therapies, primarily fasting and IV insulin. Studies have shown efficacy with fixed-rate insulin drips of between 0.05 and 0.3 units/kg/hr.3 More recently, the use of plasma exchange has shown promise in rapidly decreasing serum triglyceride levels. This has prompted smaller hospitals that don’t have apheresis capabilities to transfer these patients to larger apheresis centers.4 However, there is still a lack of substantial evidence that plasma exchange has any improved patient outcomes as compared to insulin alone. Therefore, even if your facility does not offer apheresis services, it is not unreasonable to keep this patient if they do not have other conditions necessitating transfer.

Cite this post: Jordan Feltes, MD, Arman Hussain, MD. “The Other Pancreatitis”. GW EM Blog. July 12, 2023. Available at: https://gwemblog.com/hypertriglyceridemia-pancreatitis.

Related Posts:

rMETRIQ Score: Not yet rated/21

References

- 1.Rawla P, Sunkara T, Thandra KC, Gaduputi V. Hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis: updated review of current treatment and preventive strategies. Clin J Gastroenterol. Published online June 19, 2018:441-448. doi:10.1007/s12328-018-0881-1

- 2.Santos MA, Patel NB, Correa C. Lipemic Serum in Hypertriglyceridemia-Induced Pancreatitis. J GEN INTERN MED. Published online June 2, 2017:1267-1267. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4086-y

- 3.Araz F, Bakiner OS, Bagir GS, Soydas B, Ozer B, Kozanoglu I. Continuous insulin therapy versus apheresis in patients with hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. Published online December 14, 2020:146-152. doi:10.1097/meg.0000000000002025

- 4.Insulin and Heparin Therapies in Acute Pancreatitis due to Hypertriglyceridemia. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. Published online November 1, 2021:1337-1340. doi:10.29271/jcpsp.2021.11.1337